In this article, whenever I use the word “communication,” I mean “spontaneous, unprepared, and unscripted speech.”

I recognize that we communicate with others not only through conversations but also by reading their books and watching their videos, which can be easily translated into different languages. However, in my work, I explore raw, authentic, and spontaneous expression of self in a foreign language.

Many people think I’m an English teacher. I’m not.

I don't teach the language itself. I teach speech development in a foreign language.

Not everyone can see the difference between "language" and "speech” in the context of learning a foreign language.

It is generally assumed that “language” (such as English or French) is a finite number of words and a finite set of rules for building sentences, and that “speech” is how the “language” is spoken by an individual (i.e. how the words sound when spoken by a person).

But here is the caveat: our speech is not limited to what others hear us say. There is also “inner speech”. As Noam Chomsky points out, 99% of the use of language is internal. “It takes a tremendous act of will not to think to yourself in language. Every minute of the day you’re talking to yourself.” Inner speech doesn’t involve other people and often doesn’t follow grammatical rules. It’s a deep, internal process, and we’re not always conscious of the self-talk that’s going on in our heads all the time.

It is also generally assumed that if you know enough foreign words, you can speak a foreign language. It’s thought that speech in adults doesn’t need any further development than the knowledge of words, that it happens effortlessly, freely, and spontaneously since we have already mastered it in our first language. It is assumed that what we hear in our head is what we think and that, when we tell a thought to somebody else, that person understands our thought.

Turns out, this is not the case.

Let’s say, you have a thought, and you are confident that you know exactly what you are thinking. Yet, the moment you try to put your thoughts in foreign words, it all falls apart. This can even happen in your first language. You have an idea of what you want to say, so you speak out loud, but the person listening doesn’t receive the clear thought you had in mind. Instead, all they hear is a jumble of words.

Another common scenario is this: you have a thought, but putting it in English words becomes such tedious work that you give up. You trip over your words, make others wait, and struggle to remember what you know, so you decide not to speak at all.

“Maybe next time,” you tell yourself. “When my English is better.”

If “language” was merely a set of words and grammar rules, and “speech” simply a mechanism for humans to say these words correctly, then people wouldn’t struggle so much with mastering foreign languages and expressing themselves in another language. How the words sound when they come out of your mouth is part of what “speech” is. This is why speech therapists exist. They help people with pronunciation and articulation, disfluency and other forms of stuttering, and social communication difficulties. But “speech” is more than that.

First, let’s look at what language is.

I don't teach the language itself. I teach speech development in a foreign language.

Not everyone can see the difference between "language" and "speech” in the context of learning a foreign language.

It is generally assumed that “language” (such as English or French) is a finite number of words and a finite set of rules for building sentences, and that “speech” is how the “language” is spoken by an individual (i.e. how the words sound when spoken by a person).

But here is the caveat: our speech is not limited to what others hear us say. There is also “inner speech”. As Noam Chomsky points out, 99% of the use of language is internal. “It takes a tremendous act of will not to think to yourself in language. Every minute of the day you’re talking to yourself.” Inner speech doesn’t involve other people and often doesn’t follow grammatical rules. It’s a deep, internal process, and we’re not always conscious of the self-talk that’s going on in our heads all the time.

It is also generally assumed that if you know enough foreign words, you can speak a foreign language. It’s thought that speech in adults doesn’t need any further development than the knowledge of words, that it happens effortlessly, freely, and spontaneously since we have already mastered it in our first language. It is assumed that what we hear in our head is what we think and that, when we tell a thought to somebody else, that person understands our thought.

Turns out, this is not the case.

Let’s say, you have a thought, and you are confident that you know exactly what you are thinking. Yet, the moment you try to put your thoughts in foreign words, it all falls apart. This can even happen in your first language. You have an idea of what you want to say, so you speak out loud, but the person listening doesn’t receive the clear thought you had in mind. Instead, all they hear is a jumble of words.

Another common scenario is this: you have a thought, but putting it in English words becomes such tedious work that you give up. You trip over your words, make others wait, and struggle to remember what you know, so you decide not to speak at all.

“Maybe next time,” you tell yourself. “When my English is better.”

If “language” was merely a set of words and grammar rules, and “speech” simply a mechanism for humans to say these words correctly, then people wouldn’t struggle so much with mastering foreign languages and expressing themselves in another language. How the words sound when they come out of your mouth is part of what “speech” is. This is why speech therapists exist. They help people with pronunciation and articulation, disfluency and other forms of stuttering, and social communication difficulties. But “speech” is more than that.

First, let’s look at what language is.

Language doesn’t express thought. Language is a mechanism for producing consciousness.

Many of our thoughts are unconscious. This is why we can’t express just any thought in words. We often need time to understand what it is that we’re thinking, and we reach this understanding only when we start thinking out loud.

Our experience of verbal communication becomes conscious when we speak or when we listen to others speak.

Let me explain.

The process of using language is not as straightforward as:

1) I think a thought

2) I express it out loud using language

3) I’m fully conscious of the process.

Our neural cognitive activity is essentially unconscious. The conscious experience of verbal communication is, at its core, a sensory phenomenon. We think through sensory images. In my work, I refer to them as “Mental Images” because we quite literally “see” what we say, read, or hear. We imagine it vividly.

We can break the process of speaking in any language into three steps:

This process explains why many people experience disappointment when watching a movie adaptation of a book. They “saw” the main characters differently while reading, even though the book had no pictures.

The process of converting written text into sensory images is easy to observe in adults learning a foreign language. They truly understand what they read not when they’ve translated every word, but when they can “see” it (they imagine it and feel it in their bodies). Translating is often not enough to grasp the full meaning, especially when we work with fiction and complex stories. Even if students have translated every word, they may still struggle to understand how all the words connect to create meaning. Only “seeing” what’s going on in their minds creates an unshakable experience of understanding something deeply and consciously.

Many scholars agree that language is a tool to translate thought into consciousness. We become aware of our own thoughts when we put them into words.

That’s why thinking out loud in class is such a powerful metacognitive strategy. It helps students understand their own thinking. It’s also why we talk to ourselves, even if it’s not always out loud. For example, we journal to make sense of our thoughts and experiences. We don’t write to be understood by others. We write to understand ourselves.

The self-talk that we experience as internal verbal communication is how we explain our own thoughts to ourselves, making them conscious.

Sensory images are usually accompanied by words. This is how we create meaning. “For humans, verbal communication has become so dominant that sensory consciousness is often not experienced as genuinely conscious when it is not accompanied by covert or overt spoken language” (A. Peper).

Here is an example:

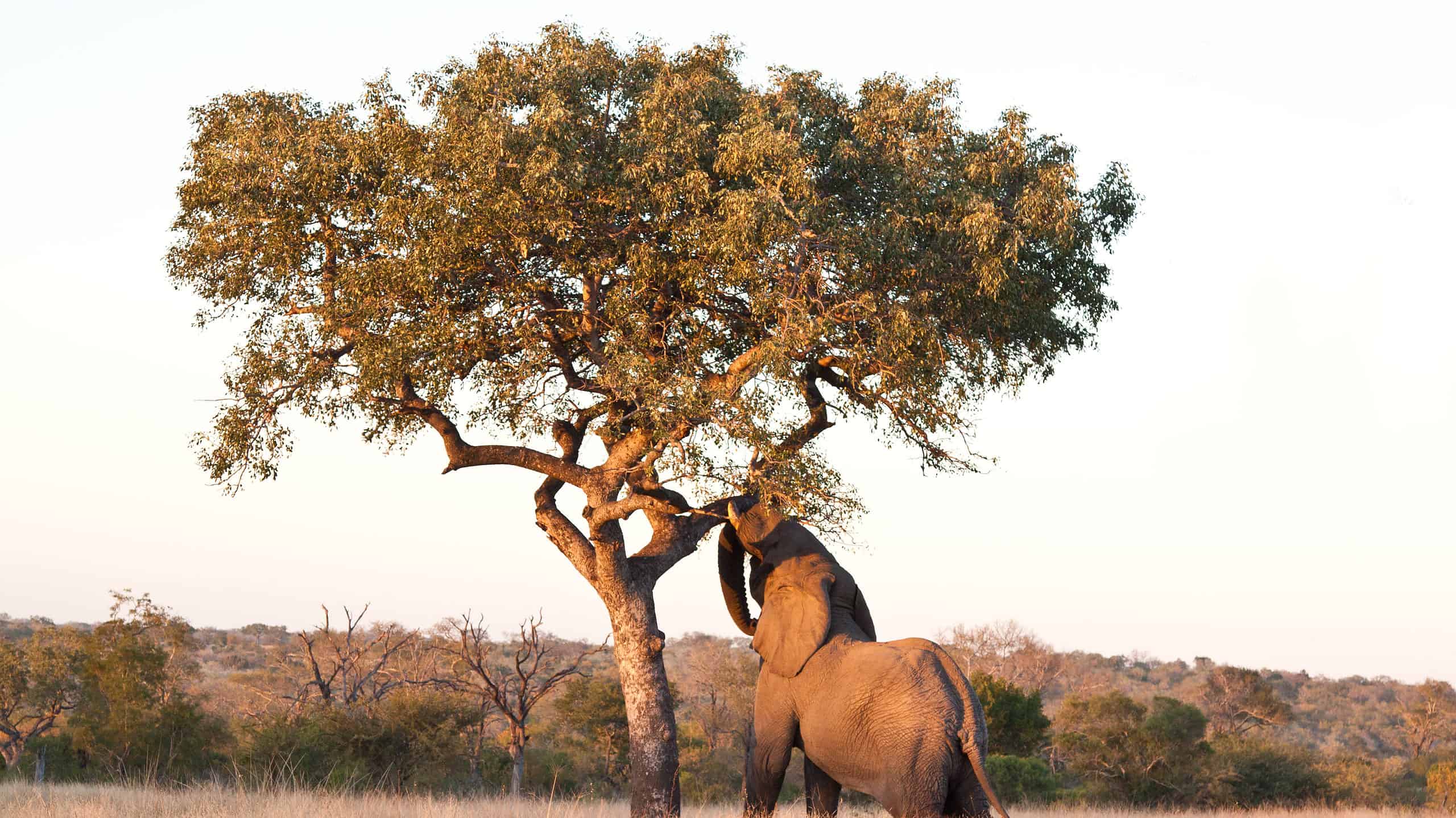

"An animal might look at a tree and experience it consciously. For a human, a tree usually becomes completely conscious only if a thought about the tree – or rather, a thought about the experience of seeing the tree – is put into words. The verbally expressed thought can then be communicated to others, which is a major goal in human life. For humans, just seeing a tree often does not meet the requirements of their world, which is based on interpersonal communication." (A. Peper)

Our experience of verbal communication becomes conscious when we speak or when we listen to others speak.

Let me explain.

The process of using language is not as straightforward as:

1) I think a thought

2) I express it out loud using language

3) I’m fully conscious of the process.

Our neural cognitive activity is essentially unconscious. The conscious experience of verbal communication is, at its core, a sensory phenomenon. We think through sensory images. In my work, I refer to them as “Mental Images” because we quite literally “see” what we say, read, or hear. We imagine it vividly.

We can break the process of speaking in any language into three steps:

- We think (unconscious cognitive activity)

- We become conscious of our thoughts when we perceive them as sensory images (‘see’ what we have thought)

- We say the words. We translate sensory images into words when we speak, and vice versa; when we read or listen to others, we translate words into sensory images to make sense of what we heard or read.

This process explains why many people experience disappointment when watching a movie adaptation of a book. They “saw” the main characters differently while reading, even though the book had no pictures.

The process of converting written text into sensory images is easy to observe in adults learning a foreign language. They truly understand what they read not when they’ve translated every word, but when they can “see” it (they imagine it and feel it in their bodies). Translating is often not enough to grasp the full meaning, especially when we work with fiction and complex stories. Even if students have translated every word, they may still struggle to understand how all the words connect to create meaning. Only “seeing” what’s going on in their minds creates an unshakable experience of understanding something deeply and consciously.

Many scholars agree that language is a tool to translate thought into consciousness. We become aware of our own thoughts when we put them into words.

That’s why thinking out loud in class is such a powerful metacognitive strategy. It helps students understand their own thinking. It’s also why we talk to ourselves, even if it’s not always out loud. For example, we journal to make sense of our thoughts and experiences. We don’t write to be understood by others. We write to understand ourselves.

The self-talk that we experience as internal verbal communication is how we explain our own thoughts to ourselves, making them conscious.

Sensory images are usually accompanied by words. This is how we create meaning. “For humans, verbal communication has become so dominant that sensory consciousness is often not experienced as genuinely conscious when it is not accompanied by covert or overt spoken language” (A. Peper).

Here is an example:

"An animal might look at a tree and experience it consciously. For a human, a tree usually becomes completely conscious only if a thought about the tree – or rather, a thought about the experience of seeing the tree – is put into words. The verbally expressed thought can then be communicated to others, which is a major goal in human life. For humans, just seeing a tree often does not meet the requirements of their world, which is based on interpersonal communication." (A. Peper)

How many times have you walked past a tree or another object without really noticing it, even though you definitely saw it? How many times did you become aware of a tree only after reading about its history and significance in a travel brochure? How many times did you realize a tree's height or origin only when someone commented on it out loud, such as, "What a massive tree! The whole front yard is shaded thanks to it."

When we practice conscious reading in my classes, we always read out loud. Students usually experience a breakthrough when they become truly aware of what they have just read. Depending on their English level and the length of the text, getting there can take 5-10 attempts. They may have seen the page or read it many times before, but after we have completed the conscious reading exercise and the practice of perceiving “mental images,” they finally get to fully understand and experience the content. This transforms reading into a conscious experience, engaging not just the mind but the body as well. They see, hear, and connect to what they have read on a human level.

This conscious practice helps students not only remember foreign words and grammar structures but also consciously use them in their own speech. First, they “see” it. And they see it differently in a foreign language compared to how they “see” it in their native one. As a result, different words are often needed to convey the same experience in another language. For example, “teal” is a color that doesn’t exist as a single word in my native language. If I simply translate the word, I will never help people “see” the color I’m describing. The translation won’t be accurate enough. Similarly, “flaky” is a trait that doesn’t exist as a single word in my first language. The word “kryptonite” can’t be translated either.

When we practice conscious reading in my classes, we always read out loud. Students usually experience a breakthrough when they become truly aware of what they have just read. Depending on their English level and the length of the text, getting there can take 5-10 attempts. They may have seen the page or read it many times before, but after we have completed the conscious reading exercise and the practice of perceiving “mental images,” they finally get to fully understand and experience the content. This transforms reading into a conscious experience, engaging not just the mind but the body as well. They see, hear, and connect to what they have read on a human level.

This conscious practice helps students not only remember foreign words and grammar structures but also consciously use them in their own speech. First, they “see” it. And they see it differently in a foreign language compared to how they “see” it in their native one. As a result, different words are often needed to convey the same experience in another language. For example, “teal” is a color that doesn’t exist as a single word in my native language. If I simply translate the word, I will never help people “see” the color I’m describing. The translation won’t be accurate enough. Similarly, “flaky” is a trait that doesn’t exist as a single word in my first language. The word “kryptonite” can’t be translated either.

I didn’t grow up reading comic books. I never even held a comic book as a child. Because I never had sensory images of “Kryptonite” before I began learning English, I couldn’t initially relate to the word. I understood it only after I learned to connect it to the appropriate sensory image.

The point I’m making is that “speech” is how we use the language to bring thoughts, consciousness, and a sense of things into being—at least, this is how I approach it in my work. Speech has distinct characteristics in every language: melody, rhythm, pitch patterns, intonation, pace, vibe, energy, and more.

When adults want to improve their fluency in a foreign language, their primary goal is to be understood by others—not just when they’re prepared, but at any moment. They want to be able to speak, respond, understand, and listen to others even when they’re unprepared. They feel that to live a better quality life, they need better English skills. Life is all about people, relationships, connections.. This requires the ability to communicate spontaneously and authentically.

People come to me wanting to be understood in unplanned, real-life situations, where things are unpredictable and when they are unprepared. So we get to work on developing their spontaneous speaking skills in English. As we begin to practice full authentic expression in another language, people quickly realize that knowledge of English (as a set of words and grammar rules) isn’t enough to express thoughts, emotions, insights, or experiences.

When we speak spontaneously—in any language—the same cognitive processes take place. At first, we’re unconscious of our own thinking process. Our thoughts are sort of responses to external stimuli, and most people walk around the planet unaware of their internal thought process, even though they are constantly immersed in it. Then, we become conscious of our thoughts by perceiving sensory images. Only after that can we translate these images into language (i.e. words). These words can be intended for others, but they can also become our internal verbal communication. We might hear our own thoughts as words; we may choose to write them down in a private journal, also as words.

“Language is not a means of communication and did not evolve as a means to communicate with others,” said Noam Chomsky. “Language evolved as a mode to create and interpret thought. It’s a system of thought.” In my 18 years of teaching and learning, I have come to agree with Chomsky time and again.

The point I’m making is that “speech” is how we use the language to bring thoughts, consciousness, and a sense of things into being—at least, this is how I approach it in my work. Speech has distinct characteristics in every language: melody, rhythm, pitch patterns, intonation, pace, vibe, energy, and more.

When adults want to improve their fluency in a foreign language, their primary goal is to be understood by others—not just when they’re prepared, but at any moment. They want to be able to speak, respond, understand, and listen to others even when they’re unprepared. They feel that to live a better quality life, they need better English skills. Life is all about people, relationships, connections.. This requires the ability to communicate spontaneously and authentically.

People come to me wanting to be understood in unplanned, real-life situations, where things are unpredictable and when they are unprepared. So we get to work on developing their spontaneous speaking skills in English. As we begin to practice full authentic expression in another language, people quickly realize that knowledge of English (as a set of words and grammar rules) isn’t enough to express thoughts, emotions, insights, or experiences.

When we speak spontaneously—in any language—the same cognitive processes take place. At first, we’re unconscious of our own thinking process. Our thoughts are sort of responses to external stimuli, and most people walk around the planet unaware of their internal thought process, even though they are constantly immersed in it. Then, we become conscious of our thoughts by perceiving sensory images. Only after that can we translate these images into language (i.e. words). These words can be intended for others, but they can also become our internal verbal communication. We might hear our own thoughts as words; we may choose to write them down in a private journal, also as words.

“Language is not a means of communication and did not evolve as a means to communicate with others,” said Noam Chomsky. “Language evolved as a mode to create and interpret thought. It’s a system of thought.” In my 18 years of teaching and learning, I have come to agree with Chomsky time and again.