Noam Chomsky says that universally the cognitive activity in all humans is the same, but the way we express ourselves varies depending on the language we speak. We all think a multitude of thoughts a day and speak to ourselves all day. While we might feel as though we think in words, words are just tools to make our thoughts conscious.

As people, we have the strong impression that we are conscious of our thoughts in language. "But apparently, language is only an intermediary in the process of becoming sensorially conscious of our thoughts and the real problem then is that those thoughts cannot be expressed accurately through language” (A. Peper). Consequently, genuine expression of thought in another language can’t be achieved through direct translation.

This means that it’s impossible to effortlessly and spontaneously express yourself to others in a foreign language unless you have mastered the process of forming thought in that language.

If you don’t practice explaining things to yourself in the target language, you won’t be able to explain them to native speakers.

Many language learners tend to talk to themselves in their native language and reserve the use of the foreign language exclusively for speaking to others. As a result, they are genuinely spontaneous only in their first language, and they create conscious thought only in that language. If they don’t practice tapping into and steering their unconscious cognitive processes in another language, they will find themselves constantly translating words, because natural expression of consciousness in the target language is inaccessible to them. The conscious mind will resist and bypass the effort to send or perceive sensory images in the new language and opt for direct translation instead, which feels easier and more straightforward. This approach might work for simple tasks, such as reading a list of ingredients on an ice cream container. However, as soon as we dive into the complexity of human relationships and expressing emotions, translation methods restrict expression and never enrich it.

I work with adult language learners who have acquired a whole lot of unconscious speaking patterns without realizing it. Essentially, I’m in the business of shifting deeply ingrained patterns, which is one of most difficult tasks for a human being to do. I help people unlearn the unwanted patterns though conscious practice, and they often unconsciously resist letting go of them. What’s interesting is that these patterns are typically acquired from direct translation of thoughts from their first language.

Since 99% of people learn the language with the goal to communicate with others, and not to develop their own speech (both inner and outer speech), they hurry to communicate their thoughts before truly understanding how native speakers of the target language create and interpret thought. As a result, a lot is lost in translation. Incorrect speaking patterns form through frequent, unconscious repetition of what seemed right to the speaker, but was unclear to the listener.

Many language learners tend to talk to themselves in their native language and reserve the use of the foreign language exclusively for speaking to others. As a result, they are genuinely spontaneous only in their first language, and they create conscious thought only in that language. If they don’t practice tapping into and steering their unconscious cognitive processes in another language, they will find themselves constantly translating words, because natural expression of consciousness in the target language is inaccessible to them. The conscious mind will resist and bypass the effort to send or perceive sensory images in the new language and opt for direct translation instead, which feels easier and more straightforward. This approach might work for simple tasks, such as reading a list of ingredients on an ice cream container. However, as soon as we dive into the complexity of human relationships and expressing emotions, translation methods restrict expression and never enrich it.

I work with adult language learners who have acquired a whole lot of unconscious speaking patterns without realizing it. Essentially, I’m in the business of shifting deeply ingrained patterns, which is one of most difficult tasks for a human being to do. I help people unlearn the unwanted patterns though conscious practice, and they often unconsciously resist letting go of them. What’s interesting is that these patterns are typically acquired from direct translation of thoughts from their first language.

Since 99% of people learn the language with the goal to communicate with others, and not to develop their own speech (both inner and outer speech), they hurry to communicate their thoughts before truly understanding how native speakers of the target language create and interpret thought. As a result, a lot is lost in translation. Incorrect speaking patterns form through frequent, unconscious repetition of what seemed right to the speaker, but was unclear to the listener.

I find it fascinating that even though people learn a foreign language to communicate with others, few reach advanced levels with a real understanding of others’ perspectives or the ability to take on different perspectives. Instead, they are primarily fixated on expressing their own thoughts—translating the words they hear in their heads. They rarely practice what I call “checking understanding:” making sure that their message is not only conveyed but also correctly received. Even more rarely do they consider the importance of checking in with their listener. They are convinced that if they say it “correctly,” it has been understood.

When language learners focus on speaking “correctly,” they often choose words that match the literal translation of what they would use in their native language. Yet, they remain disconnected from the true meaning of the words they end up using.

When language learners focus on speaking “correctly,” they often choose words that match the literal translation of what they would use in their native language. Yet, they remain disconnected from the true meaning of the words they end up using.

Their thought process occurs in their first language, while their spoken words emerge in another.

Unaware of this internal conflict, they often can’t understand why their communication with native speakers isn’t very effective, even if they have a strong command of the language.

The reason lies in the fact that they aren’t using the language to create conscious thought—they’re merely translating pre-formed thoughts. As a result, they sound like someone who’s trying too hard, rather than someone who is authentically sharing what they feel and think in the moment.

Many language learners believe that they have a clear understanding of what they want to say in their first language, and so they can easily translate what they register as conscious thought from their first language into a foreign one. This base assumption is not true. People focus on translating words, but we don’t think in words; we think in sensory images. When we communicate, the words we use must evoke the right sensory images in the mind of a native speaker. If they don’t, or if the body language of the speaker doesn’t match the meaning of the word and the image it’s supposed to represent, verbal communication gets confusing.

For example, a person might like your ideas very much, but instead of nodding, smiling, and actively listening to you, they’ll keep a poker face throughout the conversation. This can be confusing, especially in situations like job interviews, where cultural interpretations of body language differ. A lot of foreign candidates will see a smile, and think it’s a “yes,” while it’s actually a polite “no.” They will see a stern face and think it’s a “no,” while it is a clear “yes.”

The reason lies in the fact that they aren’t using the language to create conscious thought—they’re merely translating pre-formed thoughts. As a result, they sound like someone who’s trying too hard, rather than someone who is authentically sharing what they feel and think in the moment.

Many language learners believe that they have a clear understanding of what they want to say in their first language, and so they can easily translate what they register as conscious thought from their first language into a foreign one. This base assumption is not true. People focus on translating words, but we don’t think in words; we think in sensory images. When we communicate, the words we use must evoke the right sensory images in the mind of a native speaker. If they don’t, or if the body language of the speaker doesn’t match the meaning of the word and the image it’s supposed to represent, verbal communication gets confusing.

For example, a person might like your ideas very much, but instead of nodding, smiling, and actively listening to you, they’ll keep a poker face throughout the conversation. This can be confusing, especially in situations like job interviews, where cultural interpretations of body language differ. A lot of foreign candidates will see a smile, and think it’s a “yes,” while it’s actually a polite “no.” They will see a stern face and think it’s a “no,” while it is a clear “yes.”

I was brought up by Soviet parents, and I can share a personal example of how this plays out.

As a child, I often heard the phrase, “много хочешь, мало получишь,” which directly translates to "If you want too much, you'll get little."

The origin of the phrase is in the Bible:

Proverbs 13:4

Lazy people want much but get little,

but those who work hard will prosper.

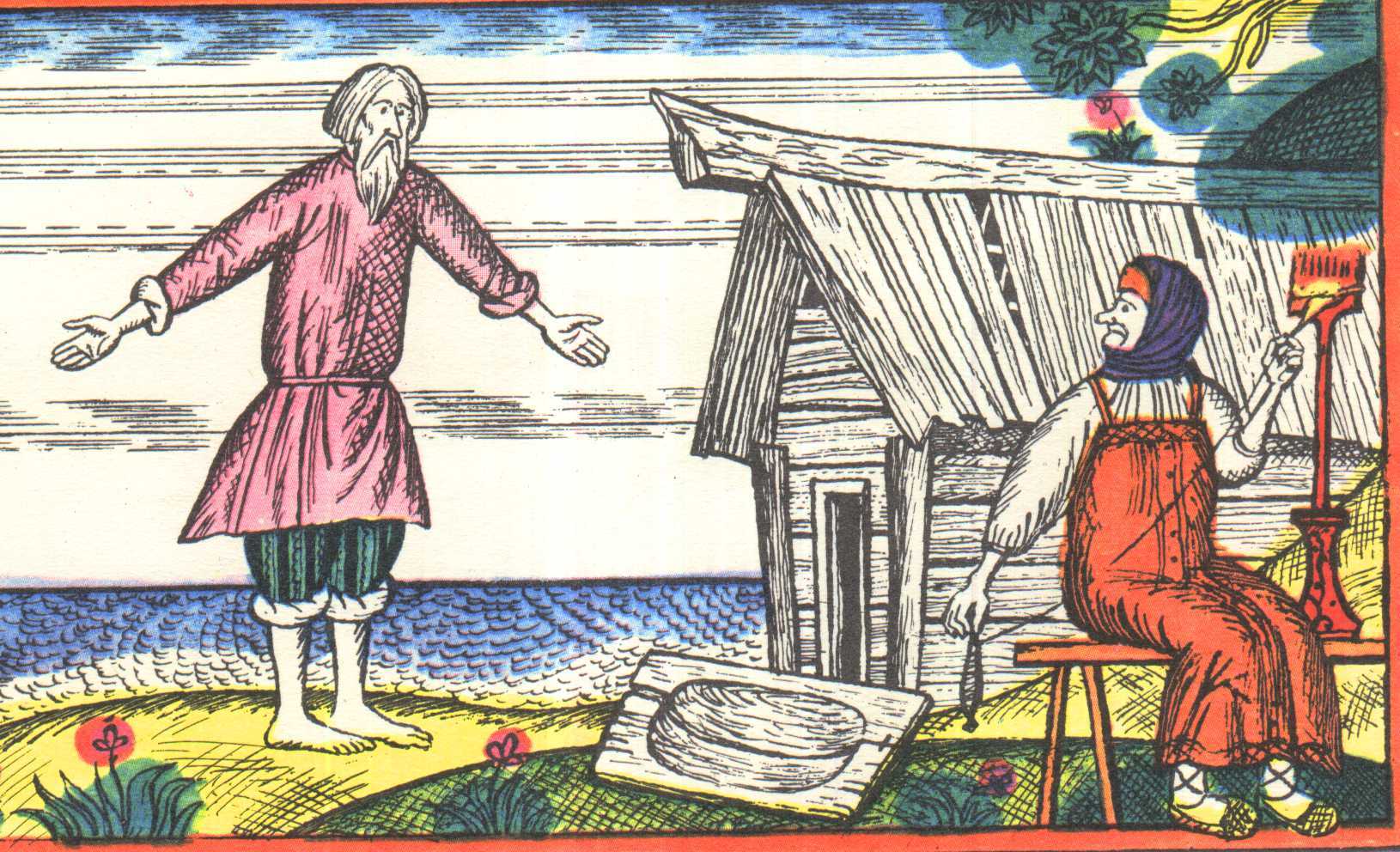

My parents, like many in the Soviet Union, never read the Bible and didn’t reference the Bible when they used the phrase. Instead, this phrase was primarily associated with the fairy tale of Alexander Pushkin “The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish,” which criticizes greed.

As a child, I often heard the phrase, “много хочешь, мало получишь,” which directly translates to "If you want too much, you'll get little."

The origin of the phrase is in the Bible:

Proverbs 13:4

Lazy people want much but get little,

but those who work hard will prosper.

My parents, like many in the Soviet Union, never read the Bible and didn’t reference the Bible when they used the phrase. Instead, this phrase was primarily associated with the fairy tale of Alexander Pushkin “The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish,” which criticizes greed.

In this tale, an old man and woman live in poverty for many years. One day, the man goes fishing and pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. Scared of the fact that a fish can speak, the old man says he does not want anything and lets the fish go. When he returns, he tells his wife about the golden fish. Angry at the wasted opportunity, she tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken. He does so, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the Queen, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

During the times of the Soviet Union, this phrase acquired an additional layer of meaning, which many explain today as “poverty mentality” or “scarcity mindset.” After the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s, even basic necessities were hard to get. Even if you wanted milk, you might have wanted too much. Milk was not always available. People would stand all day in long lines for food and often come home empty-handed.

When my parents used this phrase, they didn’t mean to lower my expectations or be less ambitious—they wanted me to recognize limits in a time of scarcity. “You want too much” meant “please understand that we can’t afford this.” Translating this phrase into English loses all these nuanced layers. For me, it instantly brings back memories of childhood and a complex cultural context that would be unfamiliar to someone who didn’t grow up in that world.

When my parents used this phrase, they didn’t mean to lower my expectations or be less ambitious—they wanted me to recognize limits in a time of scarcity. “You want too much” meant “please understand that we can’t afford this.” Translating this phrase into English loses all these nuanced layers. For me, it instantly brings back memories of childhood and a complex cultural context that would be unfamiliar to someone who didn’t grow up in that world.

This example shows how “sensory images” are dependent and limited by our personal experiences, making true fluency in a foreign language much more than just knowing the words—it’s about understanding the culture those words represent.

That’s why I encourage my community members to read fiction in English. Sensory images are often dependent on collective experiences of hundreds of generations. “In verbal communication humans refer to other people’s conscious sensory experiences from the past. When I tell somebody that it smells of autumn outside, I do not convey the conscious sensory experience of the smell of autumn I had myself, but I refer to that person’s past sensory experiences of autumn smells. In spoken language, this is the closest we can come to communicating sensory experiences…” (A. Peper)

I also offer Accent Classes for my community members. My message isn’t “fix your pronunciation.” It’s “embrace what it means to sound like a different person.” You can’t sound American if you don’t understand what it means to be American. This process helps learners explore new facets of themselves, understanding that adopting a new language doesn’t erase their original identity but adds to it. We explore the other parts of self. We don’t get rid of anything. We add new sensory images, new cognitive skills, new speaking behaviors, new movements of the tongue, new sounds, new ways to relate to others. Because we’re adding so much more to our existing identity, we need new ways to express the new parts of the self.

Now you understand how merely translating thoughts doesn’t capture their true depth, and how traditional language-learning methods skip over the crucial step of helping learners perceive and recognize sensory images.

Most language learners focus on translating prepared thoughts from one language into grammatically correct sentences in another. This works for simple situations, but not when one must answer an unexpected question, react to someone’s spontaneous emotional response, or stand up for themselves. A person will have no time to prepare a structured speech first, and then translate it to another language. In these moments, our initial response is more likely a sensory image in our first language. If that image doesn’t translate correctly into the target language, communication fails.

That’s why I encourage my community members to read fiction in English. Sensory images are often dependent on collective experiences of hundreds of generations. “In verbal communication humans refer to other people’s conscious sensory experiences from the past. When I tell somebody that it smells of autumn outside, I do not convey the conscious sensory experience of the smell of autumn I had myself, but I refer to that person’s past sensory experiences of autumn smells. In spoken language, this is the closest we can come to communicating sensory experiences…” (A. Peper)

I also offer Accent Classes for my community members. My message isn’t “fix your pronunciation.” It’s “embrace what it means to sound like a different person.” You can’t sound American if you don’t understand what it means to be American. This process helps learners explore new facets of themselves, understanding that adopting a new language doesn’t erase their original identity but adds to it. We explore the other parts of self. We don’t get rid of anything. We add new sensory images, new cognitive skills, new speaking behaviors, new movements of the tongue, new sounds, new ways to relate to others. Because we’re adding so much more to our existing identity, we need new ways to express the new parts of the self.

Now you understand how merely translating thoughts doesn’t capture their true depth, and how traditional language-learning methods skip over the crucial step of helping learners perceive and recognize sensory images.

Most language learners focus on translating prepared thoughts from one language into grammatically correct sentences in another. This works for simple situations, but not when one must answer an unexpected question, react to someone’s spontaneous emotional response, or stand up for themselves. A person will have no time to prepare a structured speech first, and then translate it to another language. In these moments, our initial response is more likely a sensory image in our first language. If that image doesn’t translate correctly into the target language, communication fails.

True fluency requires using the target language as a direct means to become aware of our thoughts, turning unconscious mental activity into conscious speech, in real-time.

To develop spontaneous speech in a foreign language, we need to practice thinking in that language. This means we need to learn to become aware of our own thoughts through speaking, not before speaking. This means consciously connecting words to images and experiences, rather than simply translating word-for-word. If we rely solely on translation, we may speak correctly, but without the sense of belonging or connection that comes from truly embodying the language. Achieving this level of fluency involves embodying the qualities of someone who speaks the language natively. It’s not just about knowing vocabulary but about understanding the emotions, cultural cues, and perspectives that shape how native speakers express themselves.

This is why my methodology includes embodiment practices, helping learners to feel the language, not just speak it. This allows them to hear comments like, “Your energy is different—it feels like I know you, reflecting a deeper connection that transcends grammar and pronunciation. We are energy when we speak. People feel our energy before they analyze our words.

When I say “language learners,” I’m referring to advanced learners who feel stuck and limited in their expression despite having strong vocabulary and grammar skills. They keep applying the same methods that got them to an advanced level, focusing on learning more of the language rather than developing the skill of spontaneous expression. To reach new heights, they must shift their focus from preparing for exams to genuinely expressing themselves.

When we express ourselves to others, we must send the sensory images that they will be able to receive and understand.

“Consciousness is part of the sensory mechanism; language, or rather the use of words, is in itself not conscious. The words are symbols referring to sensory images, which are conscious. The sound of words is of course heard consciously, but the sound is only an intermediary, a tool to excite the sensory images constituting the verbal message. Hence, verbal consciousness, i.e. consciousness evoked by the words used in talking, is essentially sensory consciousness. Referring to conscious sensory images in the listener is the way conscious thoughts are communicated verbally. It constitutes the brilliant trick verbal communication is based on.” (A. Peper)

This is why my methodology includes embodiment practices, helping learners to feel the language, not just speak it. This allows them to hear comments like, “Your energy is different—it feels like I know you, reflecting a deeper connection that transcends grammar and pronunciation. We are energy when we speak. People feel our energy before they analyze our words.

When I say “language learners,” I’m referring to advanced learners who feel stuck and limited in their expression despite having strong vocabulary and grammar skills. They keep applying the same methods that got them to an advanced level, focusing on learning more of the language rather than developing the skill of spontaneous expression. To reach new heights, they must shift their focus from preparing for exams to genuinely expressing themselves.

When we express ourselves to others, we must send the sensory images that they will be able to receive and understand.

“Consciousness is part of the sensory mechanism; language, or rather the use of words, is in itself not conscious. The words are symbols referring to sensory images, which are conscious. The sound of words is of course heard consciously, but the sound is only an intermediary, a tool to excite the sensory images constituting the verbal message. Hence, verbal consciousness, i.e. consciousness evoked by the words used in talking, is essentially sensory consciousness. Referring to conscious sensory images in the listener is the way conscious thoughts are communicated verbally. It constitutes the brilliant trick verbal communication is based on.” (A. Peper)

Noam Chomsky says that universally the cognitive activity in all humans is the same, but the way we express ourselves varies depending on the language we speak. We all think a multitude of thoughts a day and speak to ourselves all day. While we might feel as though we think in words, words are just tools to make our thoughts conscious.

As people, we have the strong impression that we are conscious of our thoughts in language. "But apparently, language is only an intermediary in the process of becoming sensorially conscious of our thoughts and the real problem then is that those thoughts cannot be expressed accurately through language” (A. Peper). Consequently, genuine expression of thought in another language can’t be achieved through direct translation.

In conclusion, studying a foreign language will never yield satisfying results if the goal is to express ourselves fully, spontaneously, and authentically in a foreign language. We must direct our efforts to developing speech in the target language (both inner and outer speech). This means, we must practice the creation of conscious thought in the target language.

Spontaneous speech development, as well as the concept of sensory images is often neglected because it can’t be standardized or easily measured. It’s also practically impossible to teach in a traditional classroom setting. Yet it is the key to moving from merely speaking a language to truly living in it. It’s why I’ve dedicated my work to developing and sharing tools that enable this kind of fluency. The methodology exists, the community of people who practice it exists, and I am the living proof that it works.

References:

On Language and Humanity: In Conversation With Noam Chomsky, August 12, 2019.

Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguistics, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Human Consciousness: Where Is It From and What Is It for, Boris Kotchoubey 1,*

Science, Mind, and Limits of Understanding, Noam Chomsky

A general theory of consciousness II: The language problem, Abraham Peper

As people, we have the strong impression that we are conscious of our thoughts in language. "But apparently, language is only an intermediary in the process of becoming sensorially conscious of our thoughts and the real problem then is that those thoughts cannot be expressed accurately through language” (A. Peper). Consequently, genuine expression of thought in another language can’t be achieved through direct translation.

In conclusion, studying a foreign language will never yield satisfying results if the goal is to express ourselves fully, spontaneously, and authentically in a foreign language. We must direct our efforts to developing speech in the target language (both inner and outer speech). This means, we must practice the creation of conscious thought in the target language.

Spontaneous speech development, as well as the concept of sensory images is often neglected because it can’t be standardized or easily measured. It’s also practically impossible to teach in a traditional classroom setting. Yet it is the key to moving from merely speaking a language to truly living in it. It’s why I’ve dedicated my work to developing and sharing tools that enable this kind of fluency. The methodology exists, the community of people who practice it exists, and I am the living proof that it works.

References:

On Language and Humanity: In Conversation With Noam Chomsky, August 12, 2019.

Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguistics, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Human Consciousness: Where Is It From and What Is It for, Boris Kotchoubey 1,*

Science, Mind, and Limits of Understanding, Noam Chomsky

A general theory of consciousness II: The language problem, Abraham Peper